Saadi Shirazi (1210-1291), better known by his pen-name as Saadi (سعدی), was one of the major Persian poets of the medieval period. He is not only famous in Persian-speaking countries, but has also been quoted in western sources. He is recognized for the quality of his writings and for the depth of his social and moral thoughts. Saadi is widely recognized as one of the greatest masters of the classical literary tradition.

A native of Shiraz, his father died when he was an infant. Saadi experienced a youth of poverty and hardship, and left his native town at a young age for Baghdad to pursue a better education. As a young man he was inducted to study at the famous Nezamiyeh Center of Knowledge, where he excelled in Islamic sciences, law, governance, history, Arabic literature, and Islamic theology.

The unsettled conditions following the Mongol invasion of Kharazm and Iran led him to wander for 30 years abroad through Anatolia, Syria, Egypt and Iraq. In his work he also refers to his travels in Pakistan, India and Central Asia. He also performed the pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina and visited Jerusalem. It is believed that Saadi may have also visited Oman and other lands south of the Arabian Peninsula. Saadi traveled through war wrecked regions from 1271 to 1294. Due to Mongol invasions he lived in desolate areas and met caravans fearing for their lives on once lively silk trade routes. Saadi lived in isolated refugee camps where he met bandits, Imams, men who formerly owned great wealth or commanded armies, intellectuals, and ordinary people. He sat in remote teahouses late into the night and exchanged views with merchants, farmers, preachers, wayfarers, thieves, and Sufi mendicants. For twenty years or more, he continued the same schedule of preaching, advising, and learning, honing his sermons to reflect the wisdom and foibles of his people. Saadi was captured by Crusaders at Acre where he spent 7 years as a slave digging trenches outside its fortress. He was later released after the Mamluks paid ransom for Muslim prisoners being held in Crusader dungeons.

When he reappeared in his native Shiraz he was an elderly man. Saadi was not only welcomed to the city but was respected highly by the ruler and enumerated among the greats of the province. The remainder of Saadi's life seems to have been spent in Shiraz.

His best known works are Boostan (The Orchard) completed in 1257 and Golestan (The Rose Garden) in 1258. Boostan is entirely in verse and consists of stories aptly illustrating the standard virtues recommended to Muslims (justice, liberality, modesty, contentment) as well as of reflections on the behavior of dervishes and their ecstatic practices. Golestan is mainly in prose and contains stories and personal anecdotes. The text is interspersed with a variety of short poems, containing aphorisms, advice, and humorous reflections. Saadi demonstrates a profound awareness of the absurdity of human existence. The fate of those who depend on the changeable moods of kings is contrasted with the freedom of the dervishes.

Saadi is well known for his aphorisms, the most famous of which, Bani Adam, in a delicate way shows the essence of Ubuntu and calls for breaking all barriers between the human beings:

Human beings are members of a whole,

In creation of one essence and soul.

If one member is afflicted with pain,

Other members uneasy will remain.

If you've no sympathy for human pain,

The name of human you cannot retain.

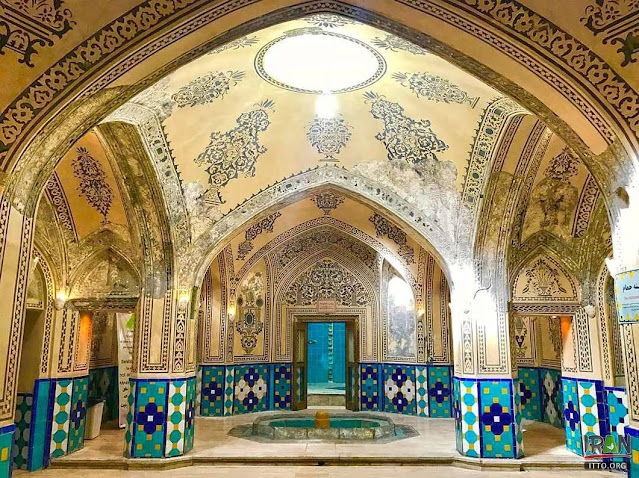

Saadi is buried in Shiraz in a mausoleum with walls inscribed with his work in tile. Set in a pleasant garden, the present tomb was built in 1952 (with inspiration from Isfahan’s Chehel Sotoun) and replaces an earlier much simpler construction. It contains eight brown columns up front with the main structure made of white marble. Unlike the outer structure. the interior is octagonal in shape. Saadi’s tomb lies in the octagonal room whereof the walls are inscribed with snippets of Saadi’s work while the 8th provides information regarding the construction of the mausoleum. To the left is a separate room housing the tomb of a Safavid era poet. The complex contains an outdoor pool running parallel to the left wing where people can throw coins into the water and make a wish. There is also an octagonal indoor pool, covered by a windowed octagonal roof. Since 2009, 50 toman coins in Iran are adorned with Saadi’s Mausoleum on them.

.jpg)

%20-%20Darvazeh%20Dolat%20Tehran.jpeg)

%20-%20Darvazeh%20Dolat%20Tehran.jpg)

%20-%20Saadi%20Square%20Semnan.jpg)

%20-%20Saadi%20Street%20Mashad.jpg)

.jpg)

%20-%20Saadi%20Square%20Iranshahr.jpeg)

.jpg)